******

This months events have been cancelled due to the Corana Virus Panic

--------------------------

Any changes will be sent out first to our email list. If you are not on the list and want to be, please send your email.

Click here for Calendar/Schedule

#######

EAA Chapter 1279 Meeting

Cancelled

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Story of the Fallbrook

Community Air Park by Stuart Marshall January, 1990

Click

Here for

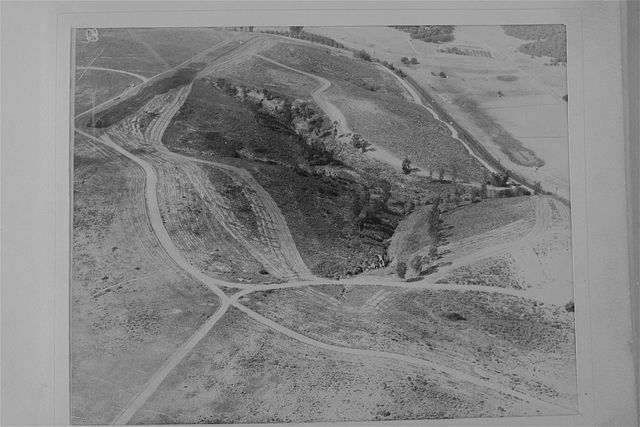

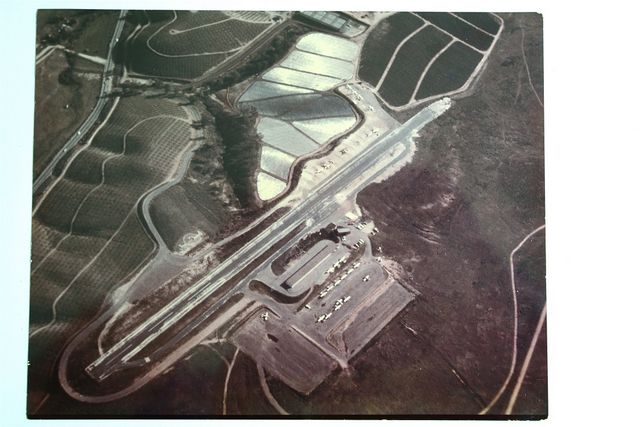

All Pictures The story of the Fallbrook Community Airport is is a saga of individual initiative, persistence and the incredible, though sometimes plodding, drive of a handful of people to fulfill a dream. The airpark's creation and development was truly an operation whereby the air-minded folks of Fallbrook literally pulled themselves up by their bootstraps. The airpark was planned and built by individual volunteer effort and with all financing generated by the founders themselves. The airpark was developed entirely without monies from federal, state, city or county sources. It took five years from the original inception until the landing strip came into existence and five more years to reach a point where the airport could be considered on a sound footing. To develop an airport without government grants has been almost unheard of since the avalanche of requests for government financial aid began after World War II. In 1959, Fallbrook was a healthy, growing community, proud of its agricultural and rural heritage. The population was in the neighborhood of 14,000. The area, however, was somewhat cut off from the greater Los Angeles and Orange County metropolis. Camp Pendleton had the squatters rights and the only way people to the north could drive to Fallbrook was to overshoot by driving further south than necessary and then coming back east and north. The highway to the east (State Highway 395) was then a narrow two-lane road. At that time, three Fallbrook businessmen were flying light planes out of Oceanside Airport, then a dirt strip. These were David Donath, an electrical contractor; Stu Marshall, an insurance broker; and Paul Casteel, who operated an appliance sales and service store. Two more pilots: Jim Wayman, a realtor, and Roger Gleason, a rancher who was a flight instructor, were flying out of a small dirt strip in San Marcos. This latter landing field was located on Lee Garner's chicken ranch. Lee had been a flight instructor in the Air Corps at Hemet, California, during World War II. Lee's ranch is now saturated with industrial buildings. A sixth person from Fallbrook, Ralph Meredith, also an electrical contractor, owned a light plane and was flying out of the newly-developed Palomar Airport in Carlsbad. In short, all were flying out of fields 40 to 45 minutes driving time away in dense traffic on two-lane roadways. None of thse fields had rental cars available in those days for businessmen, contractors, salesmen, etc., who were flying into Fallbrook. A number of businesses and institutions had a need for business and professional people to fly into Fallbrook; the Fallbrook Hospital, Fallbrook Public Utility District, and Rainbow Municipal Water District, for example. In addition, a surprising number of airline pilots had taken up residence in Fallbrook and were desirous of commuting by light plane. By early 1960, Dave Donath and Stu Marshall were granted an "airport permit" by the State of California to build an airport some six miles southeast of Fallbrook on some land leased from a private individual located in the vicinity of Highway 76 and I-15 (then State Highway 395). This airport was never built as the site was marginal. Airplanes circling to land would be flying their downwind leg eastbound, just a few hundred feet above the homes on the high ridges on both sides of the San Luis Rey River Valley. However, flying toward the clear air of Fallbrook from Oceanside, it was obvious that the ideal site would be a high ridge just south and west of downtown Fallbrook. Building the strip on this ridge would put planes several hundred feet above the normal pattern altitude on downwind over the surrounding terrain. The site was clear of obstructions, reasonably lined up with prevailing winds, and was known for its clear weather. There was a "zinger." Although unused, the land belonged to the U.S. Navy, a portion of the Naval Weapons Station on the back side of Camp Pendleton. This friendly, bare land beckoned to the aviators much as the song of the sirens attracted the sailors of the Illiad and the Odyssey. At this time, Wayman and Marshall joined forces and started a drive to lease this acreage which turned out to be 294 acres. However, the Navy was not interested in leasing. Although they didn't know it when they started, Wayman and Marshall would struggle for five more years before the airport became a reality. To get started they enlisted the help of progressive Fallbrook residents and began a campaign to wear down the Navy with letters, phone calls, personal visits, and plain old political pressure. Both Wayman and Marshall were mildly active in local Republican politics. During this period, Marshall was president of the Fallbrook Young Republicans and Republican Congressman James B. Utt had been a guest in his house on two occasions prior to speaking at the annual Fallbrook Republican Barbecue at Live Oak Park. Right in this period sometime, Wayman flew Congressman Utt down to Alamos, Mexico, for a short vacation. The breakthrough came on March 16, 1960, when Paul D. Stroop, Rear Admiral, Bureau of Naval Weapons advised Congressman Utt that the fallow land could b surplus to the Navy and could be deeded to another public body for $1. Then Wayman and Marshall came up with a proposal. The concept was simple enough, although Wayman and Marshall were to find that the simpler the proposition, the more it confounded the bureaucrats. The Navy could deed the land to San Diego County; who , in turn, would lease the ground for 50 years to a nonprofit corporation formed by Fallbrook citizens. The county was necessary as a conduit because Fallbrook was unincorporated. This nonprofit corporation would borrow the money, with individuals as co-signers, and construct the runway. Money to pay back the loan would be generated by subleasing the land for flying, recreational and agricultural operations -- all monies being poured back into the airport. Although this concept was simple, implementing it was not. Obstacle after obstacle had to be overcome. The wheels of the government grind slowly and it was April 9, 1963, over three years later, when the San Diego Board of Supervisors accepted the deed from the U.S. Navy. In 1960, as soon as the Navy agreed to give up the land, Wayman and Marshall organized a corporation with a board of directors dedicated to developing the airport without further government help. Some of the early directors consisted of: Jim Wayman, President; Stu Marshall, Vice President; Bill Hollingsworth, then manager of the Rainbow Municipal Water District; Clark Smith, a Fallbrook CPA; Walter Beck, a highly-respected agriculturist; Edward Bragg, a realtor; Roger Gleason, an avocado grower; Mrs. Loren Casper, a rancher; Mrs. Ruth Kneifel, co-owner of a plastic irrigation supply company; Gordon Poer, owner of Fallbrook Pharmacy; and William G. Thurber, Fallbrook fire chief who had flown fabric covered biplanes into the area long before there were any official landing strips. Later, board members were added such as Ernest Gentle, Aero Publishers, Inc; Robert Ingold, a rancher in Fallbrook and Kern County; Donald Lanning, M.D.; and Charles Sawday, a rancher. The first obstacle, after the Navy acquiesced, was the County Board of Supervisors themselves. Although Messrs. Gibson, Bird, Dent, Austin and Cozens were boosting the airport from the beginning, they suddenly got cold feet. Even though they were acquiring “free land,” they wanted nothing to do with an airport in Fallbrook. The county had just completed a new airport in Carlsbad, after the old Del Mar strip was condemned for the new I-5 Freeway. One member, DeGraff Austin swore that he could drive from Fallbrook to south Carlsbad in 10 to 15 minutes. Of course, the Board of Supervisors had an Aviation Advisory Council which advised the Board that the concept was not economically feasible and should be rejected. Wayman and Marshall patiently waded through numerous meetings and finally convinced the advisory committee. The group had to admit there was enough leasing potential in 294 acres to finance a small airport. Then the Fallbrook Union High School Board entered the picture, passing a resolution opposing the airport because of its proximity to the high school. “Airplanes will be falling out of the sky,” said one board member. However, at a subsequent School Board meeting, Gordon Poer and Stu Marshall convinced a majority of the board that there was no more danger to the school than there was to any other school, as air traffic was relatively dense over all the coastal areas. Finally, in April, 1963 the County Board of Supervisors accepted the deed from the Navy. The county’s final public hearing on September 17, 1963, was still a struggle. Mr. Wayman was in Washington, D.C., and Stu Marshall addressed the Board of Supervisors representing the Fallbrook Community Airpark Board. The airpark had the backing of the Fallbrook Chamber of Commerce, the Fallbrook Board of Realtors, The Fallbrook Hospital District, the Fallbrook Fire Department, and various service clubs. It was interesting to note that Mr. Wilbur Mackey, publisher of the Fallbrook Enterprise, was actively in favor of the project even though his home and developing residential subdivision were right under the cross wind leg of the traffic pattern. The president of the High School Board addressed the Board of Supervisors and withdrew their previous objection to the airport location. Objections that were expressed to the Supervisors that day were primarily limited to a few people living right under the flight pattern who, understandably, were concerned about noise and property values. One chicken rancher directly south of the proposed runway was particularly vociferous. Although their fears turned out to be groundless, all involved pretty much understood their concern and there was no apparent bitterness about the divergent points of view. The actual date the Supervisors granted the “Special Use Permit” was October 17, 1963. This was about ten months after the State of California had granted the airport Permit. You would think that after all of this, once the County of San Diego had granted the “Special Use Permit” and the state, the “Airport Permit,” the rest would be a matter of form; but, it was not to be. It took until July, 1964, for Wayman and Marshall to hammer out a 50-year lease with the county. The County Council and leasing staff seemed to throw up one roadblock after another. Finally, the 50-year lease, now the size of a metropolitan telephone book, was forwarded to the Federal Aviation Agency for their approval on September 8, 1964. The FAA claimed jurisdiction because in the terms of the original transfer, the FAA was to determine if an airport was built and operating within the 3-year time requirement. The FAA only took until October 2, 1964, to reject the 50-year lease. This was about the only time government would move speedily. Although formed by an act of Congress to “promote and foster aviation,” it took them less than 30 days to reject the lease. This is not the only time the FAA elected to impede aviation rather than foster it. As we shall see, they came up with more mischief two more years down the road. When the Airpark Board of Directors signed the 50-year lease with the county, they started construction of the airport. Not anticipating rejection by the FAA, they turned out to be a bit premature. To legalize the airstrip being constructed, a temporary, 1-year lease was quickly negotiated, signed and filed with the County Council. In September of 1964, the Fallbrook Community Airpark Board started construction. First, however, arrangement had to be made with the Fallbrook Public Utility District for annexation and water services. An ordinance set annexation fees on a sliding scale, but the ultimate amount was over $400 per acre, amounting to a total sum of over $130,000! Because of some prior political rivalry, Jim Wayman was temporarily “persona non grata” with the Utility District Board, so Stu Marshall made the presentation to them at their open board meeting. The Utility District agreed to annex the entire 294 acres, but only collect the annexation fees piecemeal as the land was subleased in increments. They also agreed to annual installment payments over the life of the subleases--normally about 3 years. In addition, the land had to be annexed to the San Diego County Water Authority and the Metropolitan Water District, all of which took time and more meetings. Ultimately, all the annexation fees were paid. As each parcel was subleased, the subtenant was to pay some “up-front” money that would pay the first installment and initiate water service. Naturally, this meant that the airpark did not receive rent revenues for operations and other expenditures as soon as they would have liked. Water annexation fees took a good chunk out of rent receipts the first few years. How was the airport and its ancillary projects built and financed? The County of San Diego engineers had estimated a cost of about $100,000 (1964 dollars) to construct the first stage which included one mile of chain-link fencing, a dirt landing strip around 2,200 feet long and 100 feet in width. That figure also included a taxiway, level aircraft parking, and secure tiedowns for 20 planes, plus automobile parking, an access road up from Mission Road and segmented circle and windsock. The people of Fallbrook did all of this for $25,000--one-quarter of the county engineer’s estimate. Negotiation for the financing was one of the few facets of the project that was easier than expected. A new bank in Fallbrook had recently opened. This was the Bank of Fallbrook, which was later to become the Southwest Bank. In September, 1964, the airport nonprofit corporation was able to borrow $25,000 from the Bank of Fallbrook through the help of Mr. Cloys Frandell, the bank’s executive vice president. Later (1966) another $5,000 was borrowed for further improvements. A number of Fallbrook residents individually co-signed the note. Through a special arrangement, each individual’s liability was limited in the event of default so that no one person would or could be required to pay the entire note. Jim Wayman and Roger Gleason each assumed liability for $2,500 each and the others assumed liability for $1,000 each. A number of the co-signers were not pilots; for example, Mr. Leo McGuire (L&M Fertilizer), co-signed stating he considered the airport a real benefit to the community. Fortunately, all this “assumption of individual liability” was academic as the note was paid off in due course. For a while, of course, it was nip and tuck, as the FAA did not approve the 50-year lease until December, 1968. This prevented the airpark from subleasing before that date, thus depriving it of any wherewithal to pay on the note. The airpark paid the interest as it became due, but was unable to pay anything on principal as long as approval of the master lease was not forthcoming. A letter in the airpark file dated September 19, 1968, indicates the airpark was in the “dog house” with the now Southwest Bank for not paying anything on principal. Writing for the airpark, Mr. Wayman promised to pay $100 per month on interest and after June 30, 1970, to pay $400 per month, plus interest until the debt was retired. This was acceptable to the bank and , ultimately, the note and all interest was paid in full. In September, 1964, the real fun began! Construction of the airport!! Firstly, 5,000 feet of chain-link fence, topped by three strands of barbed wire, had to be constructed along the new airport/Naval Weapons Station border. The cost ran a little over $5,000. The landing strip had to run roughly southwest for normal offshore breezes and northeast for the occasional Santana desert wind conditions. The land was not flat as it consisted of two hills separated by a sizeable gully. A lot of earth had to be moved. The leading “earth sculptor” at that time was Mr. U.E. Calvert, originally from Arkansas but now a long-time Fallbrook resident and friend of Jim Wayman. “Cal” had some heavy equipment, a prosperous business and a lot of civic pride. He felt he could get the job done for a minimum cost and he did. He got a large manufacturers’ sales outlet to donate the use of some heavy “turnapulls” as a demonstration scheme. The airpark paid only the fuel bill for these. Cal himself donated some machinery and charged a minimum fee on other equipment. He didn’t lose any money, but he sure didn’t make any. For example: He agreed to knock $500 off his final bill if the airpark would promise someday to plant the steep bank supporting the threshold of Runway 18 with some sort of ground cover such as geraniums. Bob Ingold let the airport use his large portable field crop irrigation system so that some 1,000 feet of dirt could be irrigated during the night so that it “cut like butter” for Cal when he attacked it the next morning. Fortunately, the runway was about all decomposed granite which, although hard as rock when dry, cut really well and compacted nicely when wet down by the Rainbird sprinkler system. Every evening about 4 p.m. Wayman, Marshall, Paul Casteel, Bud Swearingen and others gathered at the strip to move the sprinklers and survey the progress, almost incredulous to see their dream coming to fruition. The first landing was made by Stu Marshall. By pre-arrangement, Cal telephoned Stu at his insurance office to advise him the dozer would soon be making its last pass to complete the runway. Marshall drove frantically to Oceanside, got in his plane and landed in Fallbrook--the first to do so, on October 28, 1964. He shot three landings on the fresh 2,200-foot long strip. After that, Cal fine-tuned the new access road he had hewn out, constructed a somewhat narrow taxiway, pads for the airplane tiedowns, and an airport office and a spot for the ever-necessary windsock and winged T. Thanks principally to U.E. Calvert, but also to dozens of volunteers, all of this was done for less than $25,000, even including the fence. One evening a few days later, Wayman, Marshall and others were standing by the windsock, hardly believing their handiwork, and Jim Wayman smiled and said quietly, “It’s an illegal airport you know--it hasn’t a powerline at either end.” For almost four more years, the airport struggled financially. The burden of not being able to sublease pending FAA master lease approval was tough. For example: There’s a letter in the file which was written by Mr. John L. Violet, a new pilot who learned to fly after and because of the opening of the airport. In the letter John recognized that there was a “genuine need...to raise a minimum of $1,200 to properly meet taxes, repairs, minor improvements, insurance, etc.” John suggested that each “friend of the airpark” make a voluntary contribution, He mentioned that at a board meeting the night before two pilots had donated $100 each. Yes, this was a “bootstrap” enterprise. Although stymied by the FAA, other steps proceeded with or without bureaucratic approval. Shortly after the airport was opened in 1964, two pilots, “Corky” Towne and “Bud” Orcutt, bought an old used gasoline truck, fixed it up and filled it with 80 octane and made fuel available to local and visiting pilots. Those who wanted their planes gassed up left flags on their planes and Corky and Bud gassed them up after work. Itinerant pilots could phone a posted telephone number and hope to catch someone. The system worked. In September, 1966, the bombshell....the United States of America revealed its intention to invoke a “reversion clause” in the lease and have title to 152 of the 294 acres revert to them. This knocked the legs right out from under the airpark. Right from the very beginning in 1959 the airpark proponents announced and continually emphasized their intention to sublease a portion of the property to agriculture, recreation and community interests as well as airport service operations. Only by subleasing could the airpark generate the money to build and operate the airpark without asking for government grants. Also, from the beginning the proponents announced their intention not to sublease to such commercial operations as manufacturing plants, non-aviation commercial and business developments, nor apartments or residences of any type. The only exceptions to the commercial ban were: (1) aviation services. (2) a restaurant to service incoming pilots and population in general, and (3) recreational activities such as golf, tennis or maybe bowling. The final exception to the commercial ban was, of course, agriculture and agricultural nurseries. These types of leases would (1) make land productive, in say row crops, while holding for future development. (2) steep slopes otherwise useless could be planted in orchards to help fund the airport, and (3) agriculture and recreation leases would help buffer the aviation activities from the habitational surroundings. Now the U.S. Government meant to undercut completely the airpark’s ability to generate money for the airport’s construction loan and for improvement, growth and maintenance. To understand the government’s logic a little legal background detail is necessary. After World War II a number of airports, surplus in peacetime, were sold to counties and cities for $1. This was under the Public Law No. 289, under which the property could be utilized, not only for airport purposes, but also for revenue-producing purposes to financially support the operation and maintenance and future expansion of the airport. This allowed the airport, among other things, to lease some of the acreage for agricultural purposes, for a golf course or any other activity which would be compatible with airport use, to generate revenue as well as to buffer the airport activity from the residential community. However, the zinger in Public Law No. 289 was that it was only applicable to “existing” surplus airports. The land Fallbrook received from the U.S. Navy was bare land--not an airport. Consequently, the land had to be deeded under a different law. Section 16 of the Federal Airport Act provided that surplus land deeded for an airport would automatically revert to the U.S. government if the land were not used for airport purposes within three years. Having established an active, vibrant airport in October, 1964, the Airpark Board was comfortable in their opinion that they had complied with the requirement. However, the bureaucrats, loving to split hairs, in their great wisdom decided that only 142 acres were being used for “airport purposes” and that 152 acres were not being used within the three-year period. They, therefore, announced their intent to “revert”. The Airpark board was flabbergasted. However, overcoming their original astonishment, Fallbrook swung into action. A scenario unfolded that rivaled a Jimmy Stewart movie. Firstly, the County of San Diego was prevailed upon to file suit against the United States, stopping the imminent injunction. Specifically, the county filed suit against William J. McKee, FAA Administrator; Joseph H. Tippets, Director, Western Regional FAA office; and John H. Hilton, Area Manager, FAA office in Los Angeles. A hearing was held December 1, 1966 and as luck would have it, the judge assigned was Judge Carter--the same Judge Carter who had a few years previously heard the U.S. versus Fallbrook water litigation in the Santa Margarita River water dispute. The judge did not show much tolerance for eithers’ case. In effect, he said that he could not believe the U.S. government, the County of San Diego and the people of Fallbrook could not solve the matter without resorting to the courts. He continued the hearing for 90 days, but said he expected the matter to be compromised and resolved and he did not anticipate that the parties would appear in his court again. It was, in effect, a mandate to settle the dispute immediately. Now the scene switched to the political arena. At that time the Kaiser group was in the embryo stage of developing Rancho California. They were using Fallbrook Airpark to fly in many people who were involved in the huge development. Rancho California Airport, of course, was not yet in existence. Mr. Robert Unger, the project manager, asked Jim Wayman and Stu Marshall if Rancho could help. They could. Kaiser maintained a lobbyist in Washington who, through some congressional political maneuvering, ultimately set up a meeting with General McKee, the head of the Federal Aviation Agency. This arrangement was made through the Speaker of the House. Fallbrook’s County Supervisor at the time was Robert C. Cozens, a man that was most sympathetic to the airpark. Since “Bob” Cozens was then chairman of the County Board of Supervisors, it was decided to send him to Washington, D.C., for the interview with the FAA administrator. General McKee and Supervisor Cozens settled the matter, really a very simple issue, in one discussion. The county would reconvey the entire 294 acres to the United States, who would then have a surplus airport on their hands since Fallbrook had by now been operating the airport for some three years. Since it was now a surplus airport, the United States could convey the property under Public Law No. 289, which allowed leasing the land for non-aeronautical use provided proceeds went into maintenance and development of the airport. This is the way it was worked out, although when the deal was finally consummated, the airpark ended up holding 142 acres designed for aeronautical use which contained the airstrip and aviation service area and 152 acres of “non-aeronautical use.” The months and, in fact, years of agonizing by the Fallbrook Airpark supporters were over. The title was re-deeded on December 14, 1967, clearing the way for the execution of the 50-year lease between the county and the airpark. The airpark was off and running. In September, 1967, Robert Ingold, a local rancher and pilot, leased a small tract and built 10 metal “T” hangars and leased them back to local pilots for their planes. This was the airpark’s first sublease income--$40 per month that first year. In March, 1968, a fixed-base operator, Harry and Yvonne Aberle negotiated a sublease and opened up a flying office with pilot instruction, plane rental, aviation fuel, and other aircraft services. Their son, Tom Aberle, was fully licensed by the FAA as an airplane and power plant mechanic. They also absorbed the aircraft tiedown and hangar facilities. In July, 1971, the first 40 acres were leased for strawberries. The annual rent was $4,000 of which $2,600 per year, plus interest, had to be paid to the Fallbrook Public Utility District for water service. The airpark netted about $1,000 per year for the first five years. In December 1971, a 20 -year nursery lease was negotiated on 37 acres. The first year’s rent was $5,780, but some $2,400 went to the Public Utility District with about $3,200 per year going to the airpark. The airpark was pulling itself up by its bootstraps. The next lease was in August, 1972, in which 5 acres were leased for tennis courts and other recreational activities. After water fees, the airport netted $1,380 for the first year. The folks of Fallbrook had backed the airport from the beginning. One of the reasons was that from the very start the Airpark Board had declared that the airpark was for the entire community of Fallbrook, not just pilots and businesses. Accordingly, in August, 1973, a substantial acreage was leased for $1 a year to the Youth Baseball group. Although this sacrificed a considerable income over the years, the Airpark Board felt this was a worthwhile endeavor. A facility was developed that has been used by thousands of kids and their parents over the years. Later, certain acreage was set aside for Boy Scouts and other groups for primitive camping and outing areas--also at $1 a year. The airpark’s last hurdle was also a significant problem. And this too came from the government--this time the IRS. This occurred in 1973. Although the airpark was a nonprofit corporation and all monies had been plowed back into the airport construction and improvement, the IRS was afraid that some “hanky-panky” must be going on. It cost the airpark some money as the IRS agent spent considerable time in Frank Levering’s CPA office. In the end the IRS accepted the original tax statement as filed with no changes whatsoever. Fortunately, the airpark had sought expert advice from the CPA since the very beginning. Incidentally, this would be a good time to mention that neither Jim Wayman nor Stu Marshall nor any of the other many volunteers ever took an expense reimbursement from the airpark. All the hundreds of trips to San Diego and Los Angeles, all the telephone calls, etc., were donated by the participants. The physical improvements on the airport, for example, the first few years were largely the result of just plain hard work done by Victor Vanderlinden. The airport paid for bulk oil, but Victor paved the runway, taxiway and parking areas pretty much by his efforts alone. It was not unusual to come by the airport in the late afternoon and see Victor shoveling sand on a freshly oiled area--not an easy task. With or without help, over the years he took care of most of the drainage problems of the airport. Once the IRS realized no one was lining their pockets they were impressed. When the agent left he shook Wayman’s and Marshall’s hands and congratulated them on an “almost miraculous achievement.” Desirable, outstanding communities such as Fallbrook don’t just happen. They don’t develop by serendipity. Over the years they evolve out of the dreams and then the arduous endeavors of many, many people. In most cases the problems are attacked with a mixture of altruism and some element of self-interest. Those who thought and fought to bring Colorado River water to Fallbrook, those who risked their precious capital for the first property developments, those who gambled with a new business venture back in the 40s and 50s, those who worked so hard to put our educational system on a pinnacle, all had a significant share in making Fallbrook the Fallbrook we all love. Those who pioneered the airport made their contribution---they literally pulled the airpark up by the bootstraps.

|

Copyright Friends of the Fallbrook Air Park -

Last updated 1/21/2017